Of fenced playgrounds, happy places, and contained spaces

Of fenced playgrounds, happy places, and contained spaces is a reflection from a recent field trip part of the GRABS team did to eThekwini / Durban and eGoli / Johannesburg in South Africa, in early May 2025. I wrote about this influenced by my position and experiences as a male Latino-white, South American with European roots, migrant who has had the opportunity and privilege to study, work, and travel in many places across the world. This was my first time visiting South Africa.

By Juan Manuel

It’s morning, 08h30. It’s in eThekwini / Durban city centre. And it’s on our way to Diakonia Avenue, when the taxi driver locks all four doors, tells me to put down the phone and close the car window. Outside, a child begs for money. Sat across the street, her back against a wired fence, a woman watches the child from a sidewalk – their mother? Green lights, and we cross the rail tracks. Seemingly lost, absent minded bodies walk across the streets, their eyes abated, lost in worry, their paths erratic, careless of the traffic. Dust suspended in the air, plastic trash littering the earth, unkempt, spiky shrubs and weeds on broken tiles, high uneven kerbs, defaced pedestrian crossings, and cracks on the asphalt, walls and fences topped with broken glass shards and barbed wire… Images of abandon, poverty and degradation. Reminders of insecurity and unwelcome.

Faraway, at the same time, in a community-based refugee centre at Yeoville, an inner neighbourhood of eGoli / Johannesburg, a child slides down a toboggan, another sways on a swing. Three volunteers watch the children play. It’s their coffee break, and they sit on plastic chairs on a patch of grass. Inside a classroom, a group of ten or more children ran to embrace a group of visiting and suddenly bemused and heart-warmed researchers. Reds, yellows, greens, and blues paint the sheet metal roofs and walls of containers that serve as classrooms, kitchen, workshops, and offices. Paint that distracts from, but does not conceal the high concrete walls, metal fences and barbed wires… A happy place, in a contained space.

Back to the Southeast. Now it’s in uMhlanga, KwaZulu-Natal. A jogger stops to stretch next to a bench, where someone is just waking up from rough sleeping. A coffee shop, one barista, and a queue of six impatient morning people… they don’t want to miss the sunrise. A few meters away an automatic gate and another fence. The fence is rimmed by electrified wires that run all around the compound. It makes me think of some fancy cattle enclosure. On the walls of the compound are two different private security companies’ posters: one brown and red, the other yellow and green. Outside the gate, and under a CCTV camera, a cleaner hustles with a straw-broom to sweep dead leaves, twigs, and dust off the driveway. Two Vervet monkeys jeer, hiss and fizzle… Parallel paths, segregated trajectories. Seemingly close, yet lives apart.

Fictionalised recollections, made up scenes that could, however, just as well have taken place during our research visit to South Africa. For the fenced, barbed, and enclosed playgrounds, the walls littered with private security companies’ logos, and the segregation of poor and rich, of whites and blacks1, of gated privilege and contained play and joy, of actual and perceived insecurity, of wealth and degradation, of ease and abandon, of curious monkeys and watchful cameras… they were all very real and omnipresent. Asphyxiating.

Sobering. Hard. Emotionally charged in all manner of ways. The testimonies, experiences, and knowledge shared to us spoke of day-to-day struggles, strained coping mechanisms and strategies, and jarred hopes and dreams.

There were differences between groups, ages and gender. For boys in school, it was the costs of education, the despair, lack of hope, and defeatism of the ‘what’s next’. For boys out of school, it was about education, work, costs of living, and the tensions arising between parents and families’ traditions and expectations with those of the local South African society and culture. For girls in and out of school, it was some of the same but also the expected, imposed responsibilities of housework and childcare. For young mothers, it was about the harrowing experiences and stories of sexual and gender-based violence, it was about the increasing difficulty to take risks to survive and live better in an increasingly hostile and unsafe environment.

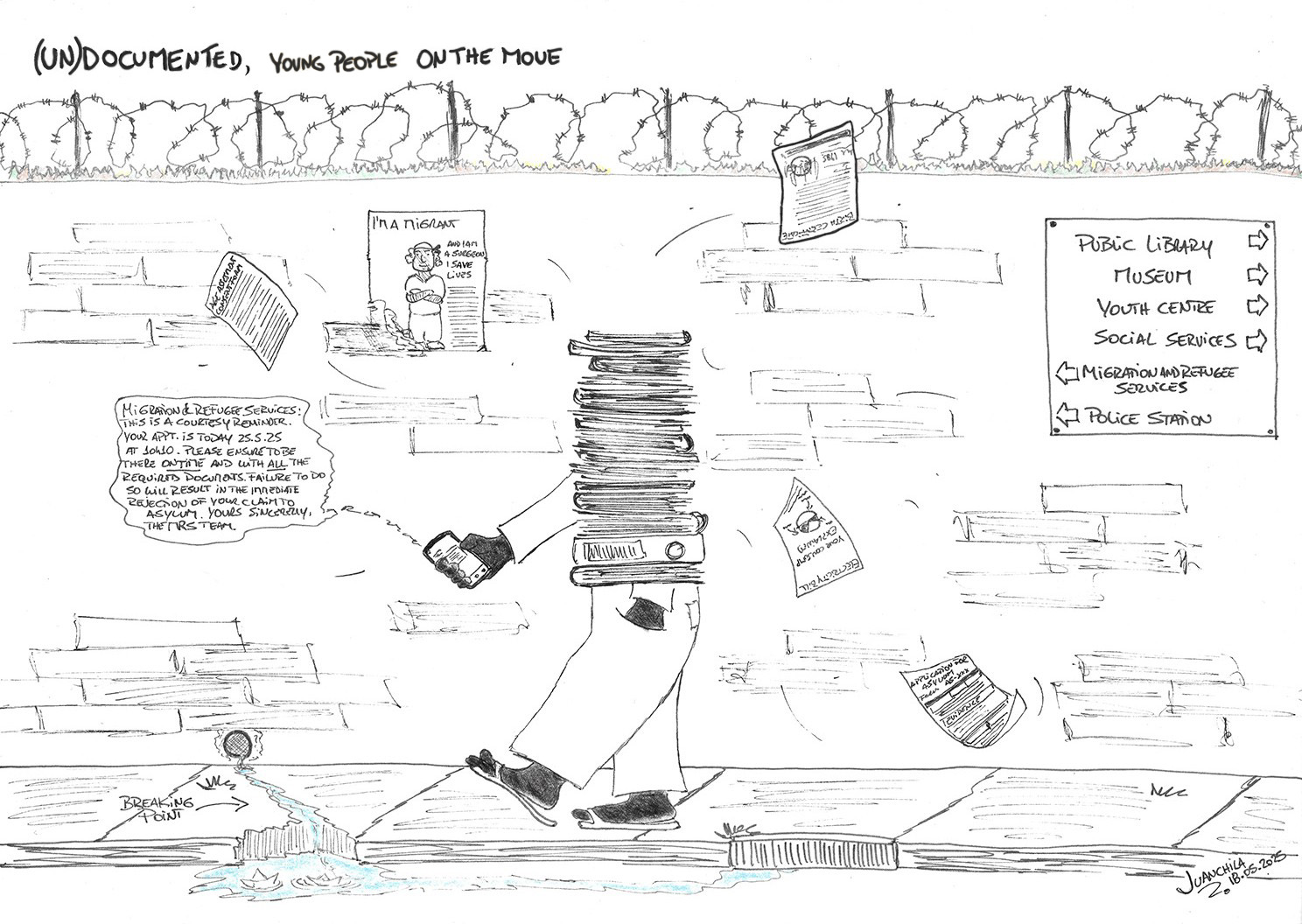

And there were common issues too. For both young men and women, there was the troubled and receding networks of support within their families and communities. A sense of nowhere to go, no one to talk things with. There were the challenges of documentation, or lack thereof, that sprawled out to every single facet of a person’s life. There was the consuming sense of insecurity and violence and mistrust of police and law enforcement authorities. The youth expressed their unease to go out to school, to work, to meet friends and family for fears of being either arrested or attacked, for exhaustion at having to confront daily micro and macro aggressions.2

There was the overwhelming sense of loss; loss of the silly, loss of the joy… It was jarring, unsettling to listen to 15-19 year olds speak with so little hope or dream for their futures, finding it much harder to talk about their silly endeavours, their tangential questionings, their self-doubts, their half-baked self-assertions. Anxieties derived also from healthcare access and the costs of medication; from prospects of education to socio-economic exclusion and marginalisation; from xenophobia and Afrophobia3 to exploitation and criminalisation.

And yet, despite all of the above, there were also a few, yet genuine and awesome moments of laughter, of stories of mobilisation and action (when one of the key informants shared their lived experiences of displacement, unlawful police arrest, and their decision to join a local Police Community Forum to initiate change from inside), of empathy and support (when a young girl talked about the support she received from local South Africans when she first arrived), of bravery (when young mothers confided their stories, when a boy spoke about his sexuality). Not everything was doom, the youth we met had projects, talents (one of them designed clothes, another was great at basketball, several others created content on various social media, some drew, some wrote poems). But those were few exceptions within mostly emotionally heavy and charged sessions… Asymmetrical maturity, fast-tracked adolescence, displaced resilience.

How, why did it get to this point? Long heralded as one of the most progressive migration and refugee regimes in the late 90s with its non-encampment and human rights based approach, the original text of South Africa’s 1998 Refugee Act provided asylum seekers and refugees collective social entitlements and access to healthcare, employment, legal protection, and other social rights.4

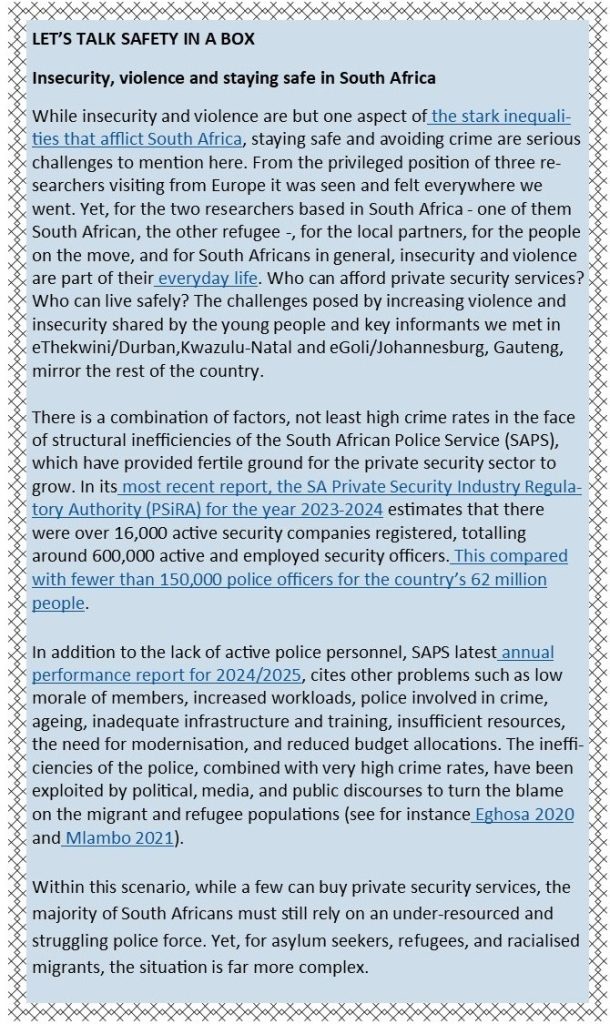

On paper many of these rights still hold, yet in practice they are not recognised. There are several reasons for this: increasing securitisation and criminalisation of migration and refugee policies and mechanisms of (im)mobility control5; inefficient and insufficient policy governance harmonisation and coordination; structural and systemic racism, exclusion and marginalisation. It would seem then, that historically colonial and Apartheid-rule policies, systems and mechanisms for the identification, categorisation and othering of ‘insiders’, ‘outsiders’ and ‘foreigners’ far from being erased, remain very much in place and have instead been redirected towards Black African outsiders.6 Today after years of restrictive amendments, the opportunities and spaces for people on the move to have a dignified, healthy, social, economic, and cultural life have dramatically shrunk.7

And yet, while the colonial, structural core factors are known, what do we know about how young people on the move traverse them. What is it like to live undocumented? What does one feel when they tell you that you are not South African despite having been born and lived in the place all your life? How do you cope day-to-day, night-to-night with social, economic, cultural, political exclusion and marginalisation? How do you navigate a space where one’s personal security is always under threat, especially if you are a woman, a sexual minority, a child, an elderly person, or a differently able person? What and how do young people on the move think could make things better?

In late July, the GRABS team will continue with fieldwork in South Africa, this time running activities and training workshops with young people. To find out more, keep an eye on our News & Activities page here.

Endnotes

- ‘of whites and blacks’… Following an important intervention from one of our SA colleagues, this sentence which I write on the back of just our ten day visit to eThekwini / Durban and eGoli / Johannesburg, requires a critical reflection. It is difficult to assert whether the stark inequalities (of property ownership, employment, mobility, security …), are an issue of race or is an issue of structural and intersectional factors (wealth, gender, race, nationality) that play out together. Wealth inequality might just be racialised or gendered. Indeed, the latest Land Audit Report published in 2017 shows big differences in land ownership in terms of race, gender and nationality. For instance, individual landowners identified as Whites own 26,663,144 ha or 72% of the total 37,031,283 ha farms and agricultural holdings, compared to 15% (5,371,383 ha) by Coloured, 5% (2,031,790 ha) by Indians, and 4% (1,314,873 ha) by Africans, with the remaining 4% (1,697,099 ha) co-owned or owned by other groups. Men also owned much more than women (72% or 26,202,689 ha compared with 13% or 4,871,013 ha). South African individuals owned 92% of the total (33,996,255 ha), while foreigners owned just 2% (769,284 ha). See Government of South Africa (2017) Land Audit Report. Phase II: Private Land Ownership by Race, Gender and Nationality. Report published by the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform, published in November 2017, Pretoria. Available here: https://www.gov.za/documents/other/land-audit-report-2017-05-feb-2018. However, the data from this report only refers to farms and agricultural holdings in South Africa. Data on real estate ownership is missing. ↩︎

- Youth’s unease relates to both perceived and actual violence, one has only to remember the hate crime and anti-migrant riots of 2008 and 2015. See Bekker, S. (2015). Violent xenophobic episodes in South Africa, 2008 and 2015. African Human Mobility Review, 1(3), 224-252. ↩︎

- We learned about the term ‘Afrophobia’ during our group discussions with the youth in Durban. Prof. Rothney Tshaka, Chair of Department: Philosophy, Practical and Systematic Theology, University of South Africa, argues that the antagonism directed towards non-South African blacks in the so-called xenophobic attacks that have erupted sporadically in South Africa in 2008 and 2015, can best be described not as ‘xenophobia’, which is fear of the other, but as ‘Afrophobia’, which is “fear of a specific other – the black other from north of the Limpopo River”. UNISA (2016) Afrophobia versus xenophobia in South Africa, UNISA News & Media, published on 15 November 2016. Available here: https://www.unisa.ac.za/sites/corporate/default/News-&-Media/Articles/Afrophobia-versus-xenophobia-in-South-Africa ↩︎

- Refugees Act 130 of 1998.See respectively Regulations 27 [G], 27 [F], 27 [B], 29. South Africa’s Refugees Act 130 of 1998, and its subsequent amendments of 2002, 2008, 2011, 2015, 2017, and 2022, can be accessed here: https://www.gov.za/documents/refugees-act; Masuku, S. (2024). Beyond the transient protections of the Children’s Act: contestations on citizenship and belonging for foreigners with refugee claims in South Africa. In Research Handbook on Asylum and Refugee Policy (pp. 267-279). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781802204599.00027 ↩︎

- Eghosa, E. J. (2020). The securitization of asylum in South Africa: A catalyst for human/physical insecurity. In Borders, Sociocultural Encounters and Contestations (pp. 112-138). Routledge; Mlambo, V. H. (2021). Irregular Migration, Cross Border Crime and the Securitization Theory: A South African Reflection. Journal of Social Political Sciences, 2(1), 12-29.https://doi.org/10.52166/jsps.v2i1.40 ↩︎

- Mpofu, W. (2020). Xenophobia as racism: The colonial underside of nationalism in South Africa. International Journal of Critical Diversity Studies, 3(2), 33-52; Mbiyozo, A. N. (2022). The Role of Colonialism in Creating and Perpetuating Statelessness in Southern Africa. African Human Mobility Review, 8(3), 75-93. ↩︎

- Further still, proposed legislation by the Department of Home Affairs, on the make for several years now and still facing legal and constitutional challenges, seeks to further limit the rights to asylum and withdraw South Africa from the 1951 Refugee Convention. Crouth, G. (2024). Home Affairs’ White Paper on migration panned for ‘playing to the crowd’ ahead of May elections, published on Daily Maverick, 19 April 2024. Available at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2024-04-19-home-affairs-white-paper-on-migration-panned-for-playing-to-the-crowd-ahead-of-may-elections/ ; Mutsila, L. (2025) Home Affairs sent back to drawing board on Refugees Act after legal setback, published on Daily Maverick, 21 May 2025. Available at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2025-05-21-home-affairs-sent-back-to-drawing-board-on-refugees-act-after-legal-setback/ ↩︎