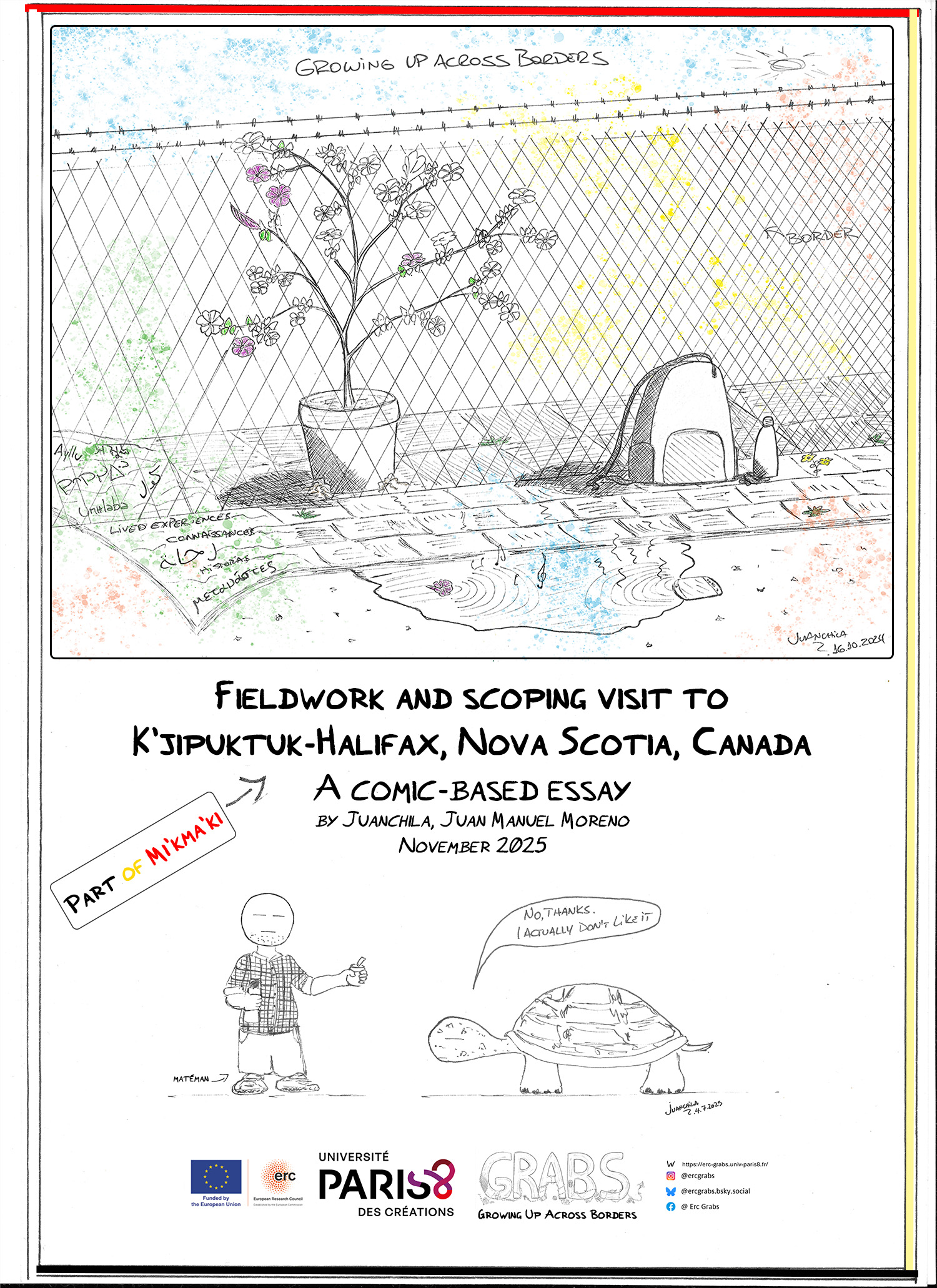

Fieldwork and scoping visit to K’jipuktuk-Halifax, NS, Canada: A Comics-based essay

This comics-based essay is both a report and a methodological exploration produced during my fieldwork and scoping visit to K’jipuktuk-Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada, between 18 July and 4 August 2025

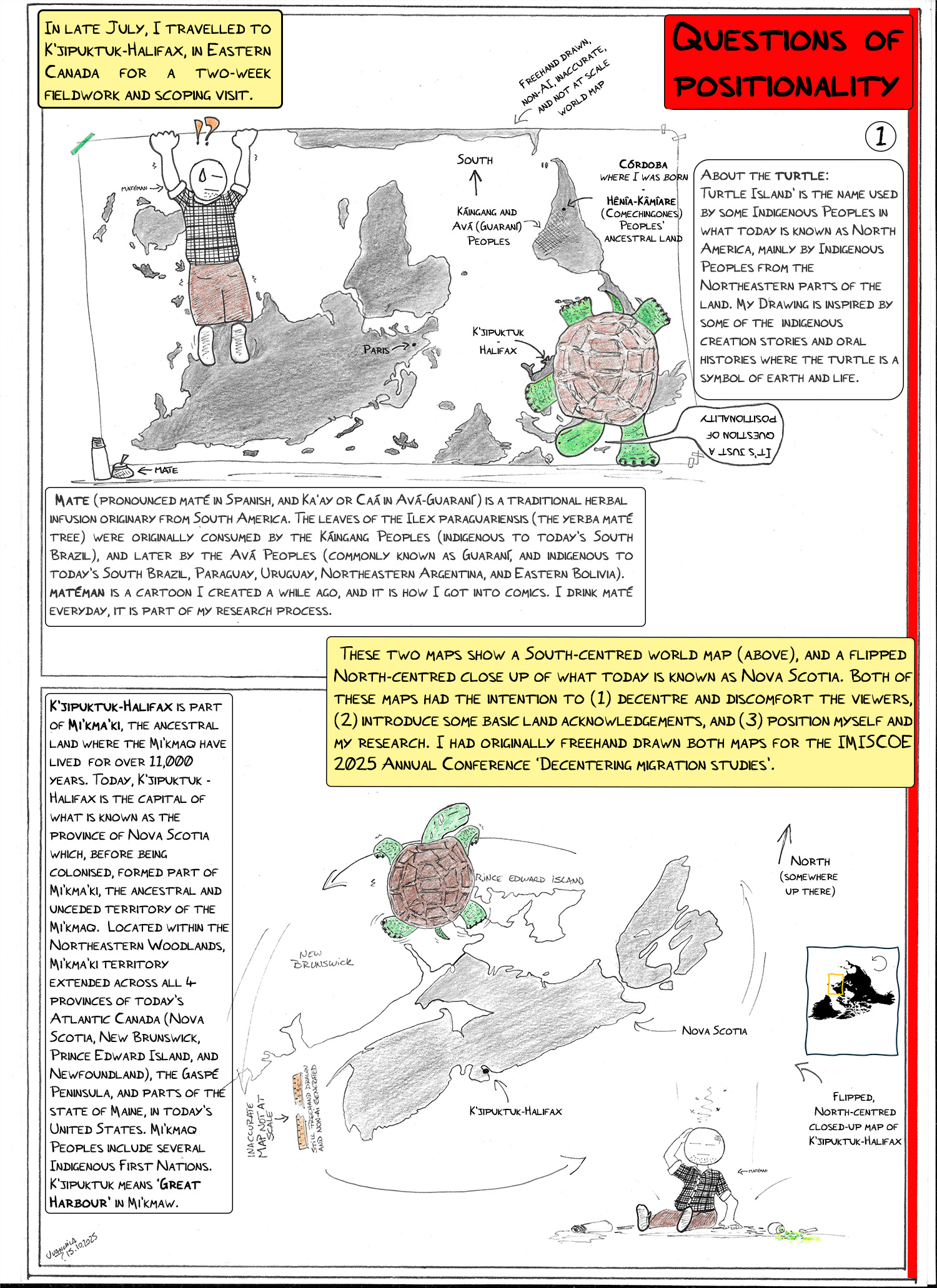

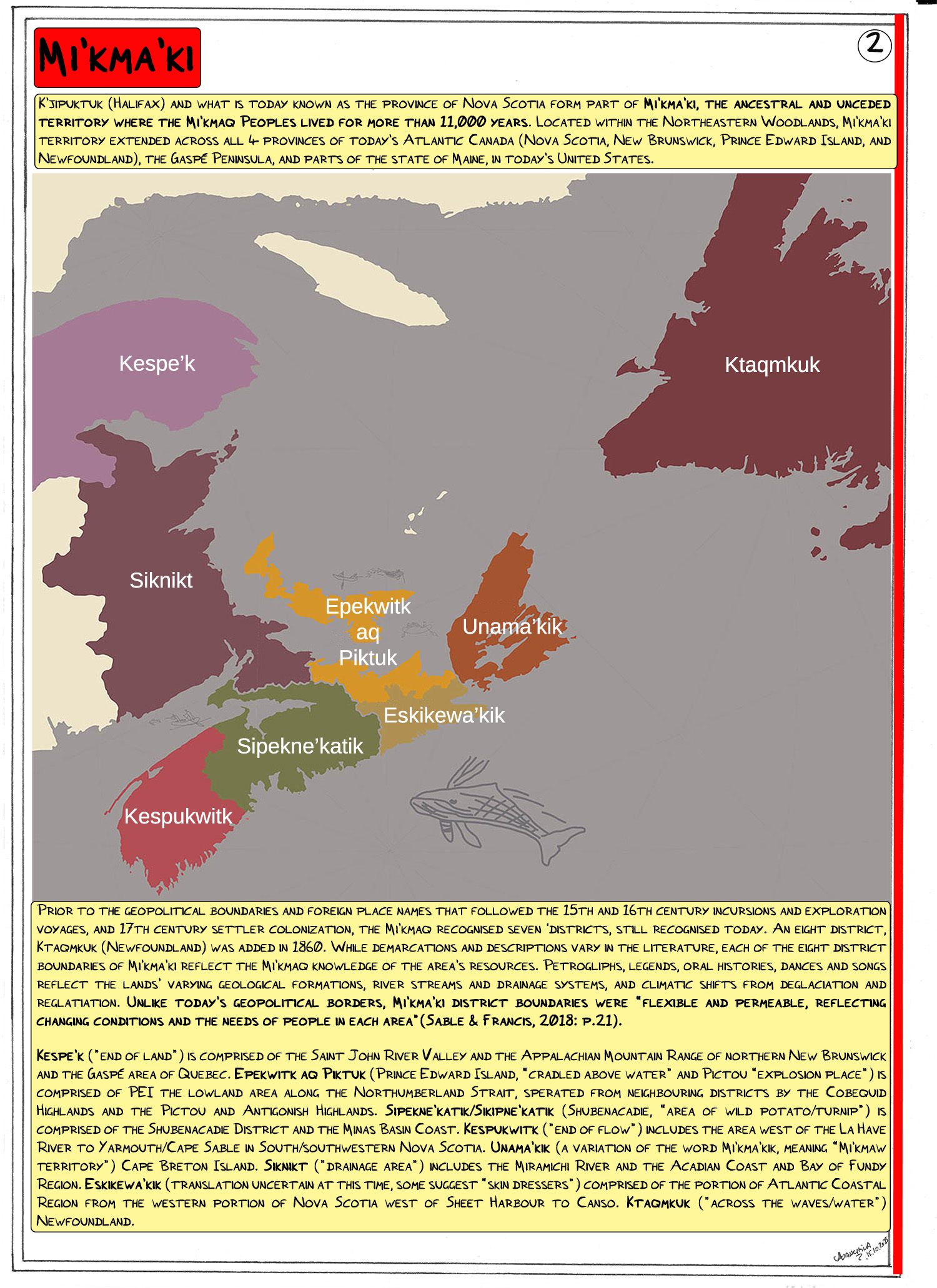

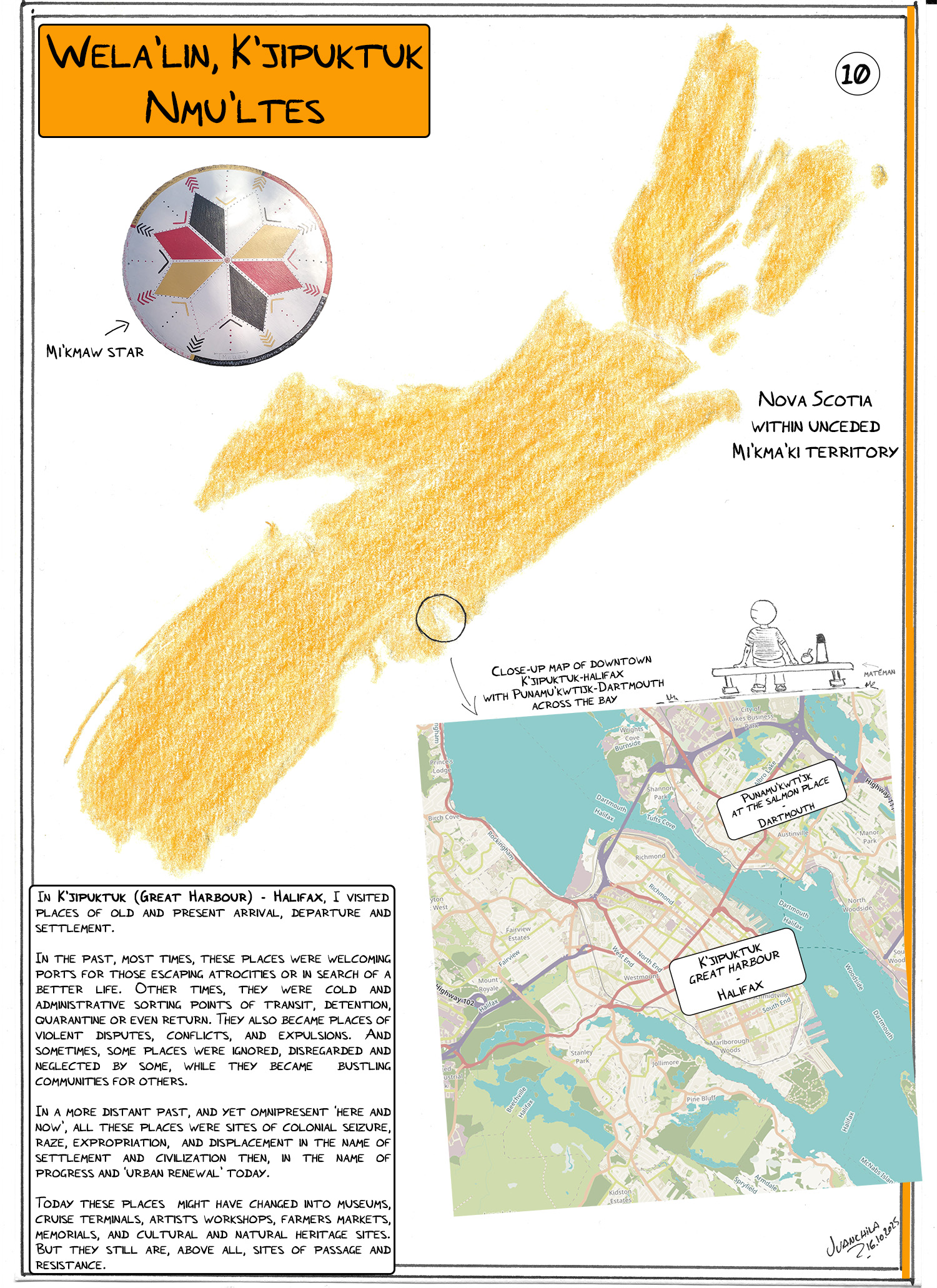

K’jipuktuk, which means “Great Harbour” in Mi’kmaw language, forms part of Mi’kma’ki, the ancestral land where the Mi’kmaq peoples have lived for over 11000 years. K’jipuktuk-Halifax is also the capital of what today is known as the province of Nova Scotia in Athlantic Canada.

Lire la version en français ici

Leer la versión en español acá

An English description and transcription of the content of this comics-based essay is available to download here

Cover

Panel 0 – Introduction

Panel 1 – Questions of positionality

Panel 2 – Mi’kma’ki

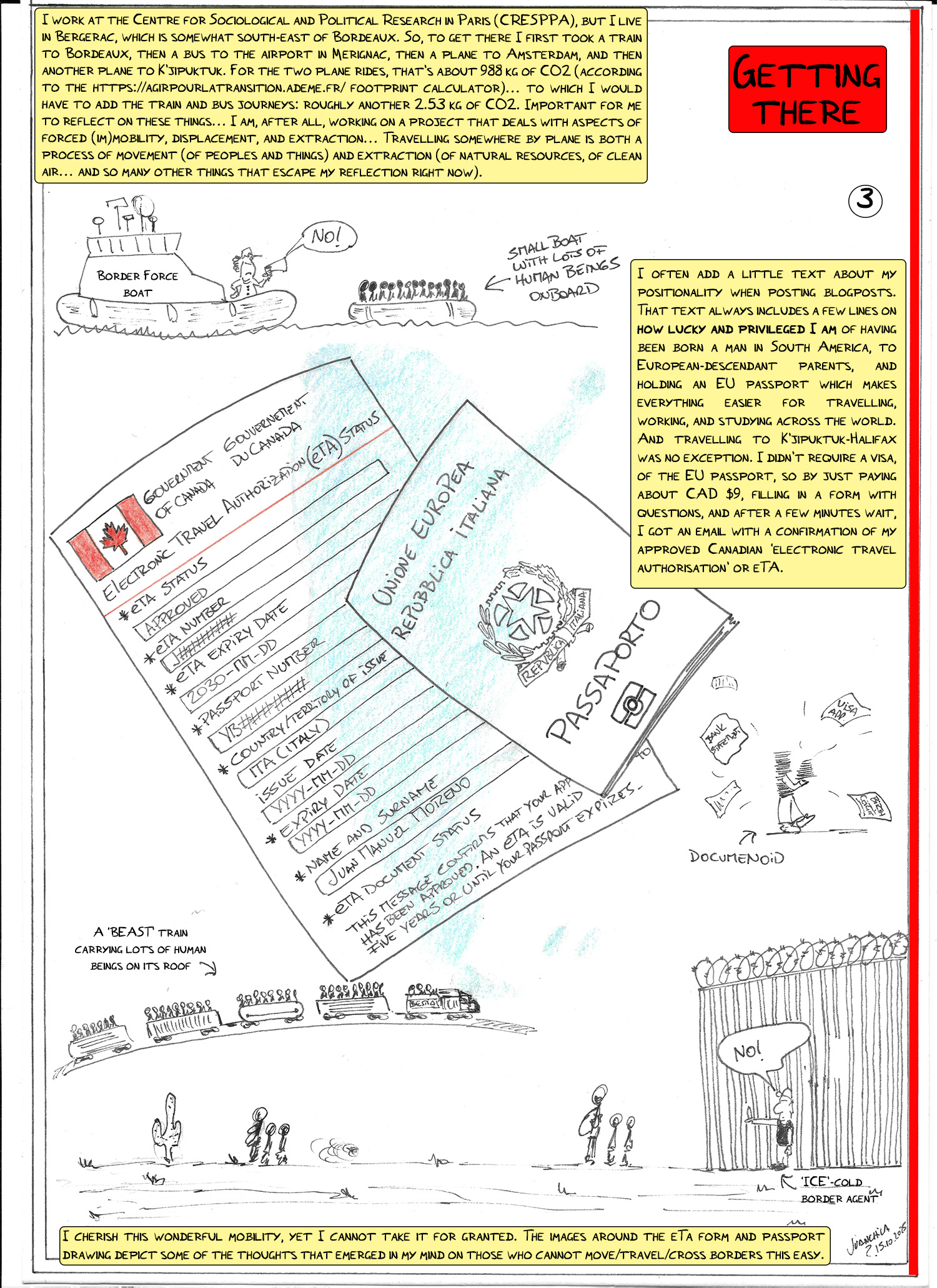

Panel 3 – Getting there

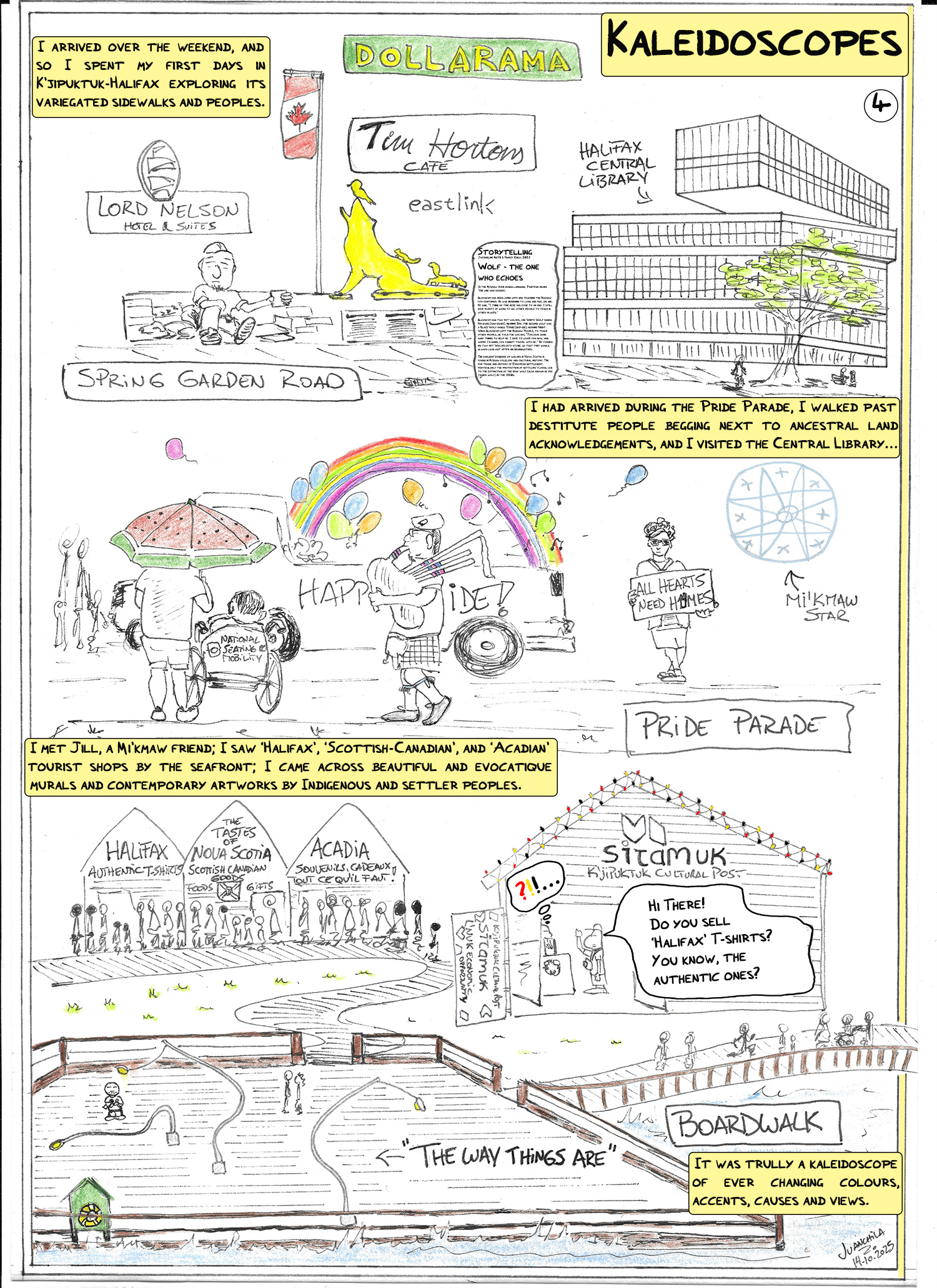

Panel 4 – Kaleidoscopes

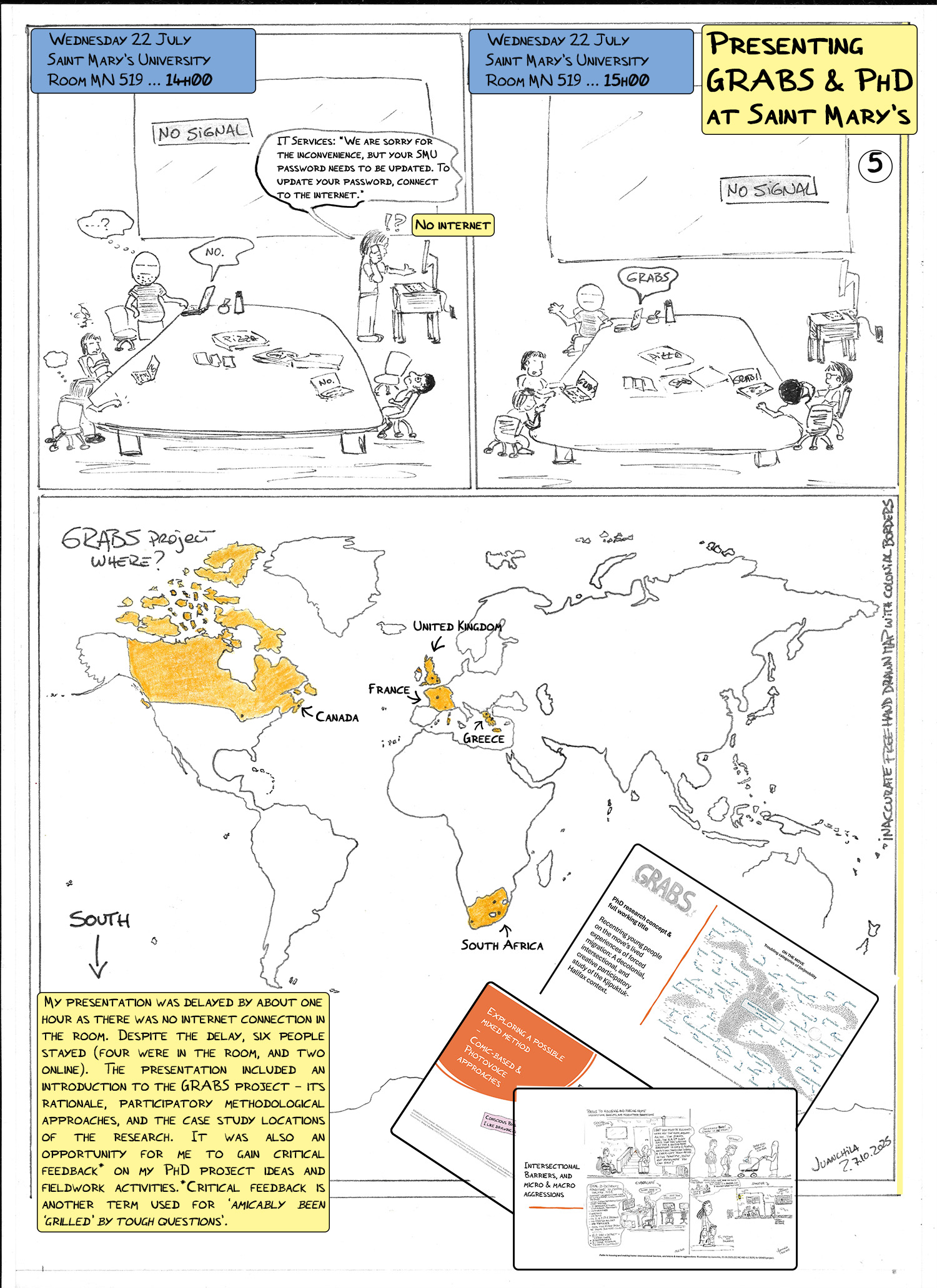

Panel 5 – Presenting GRABS & PhD at Saint Mary’s

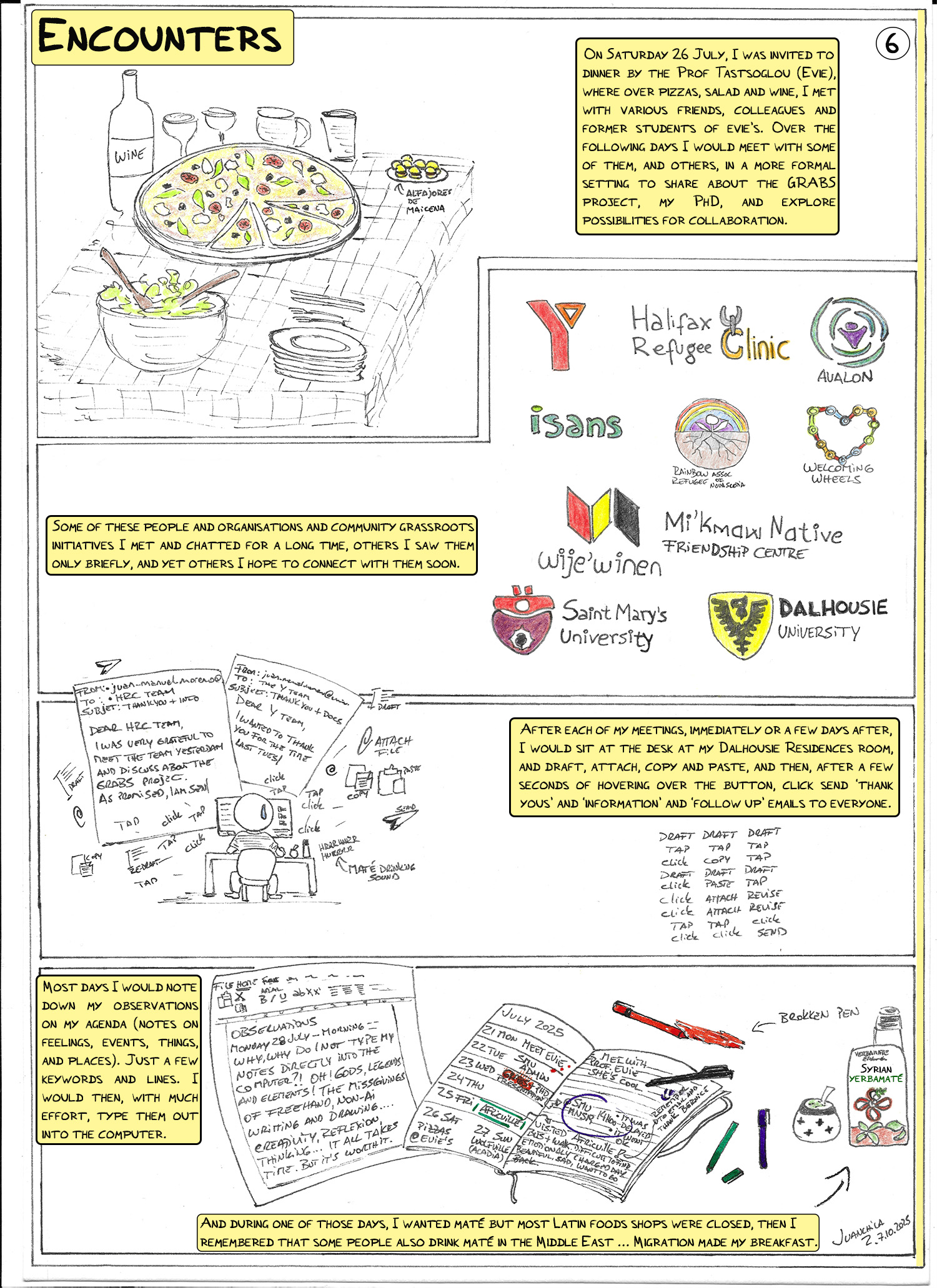

Panel 6 – Encounters

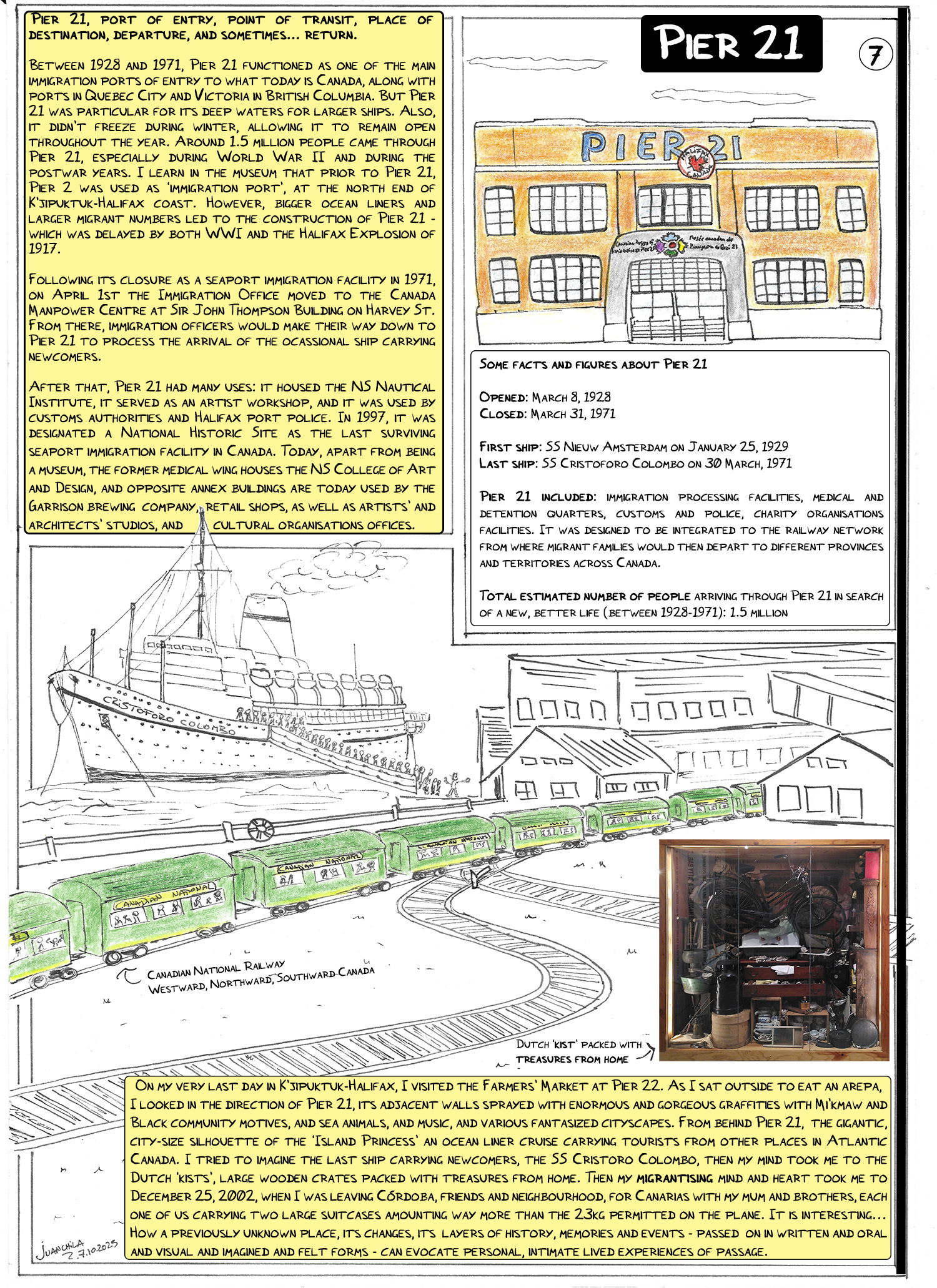

Panel 7 – Pier 21

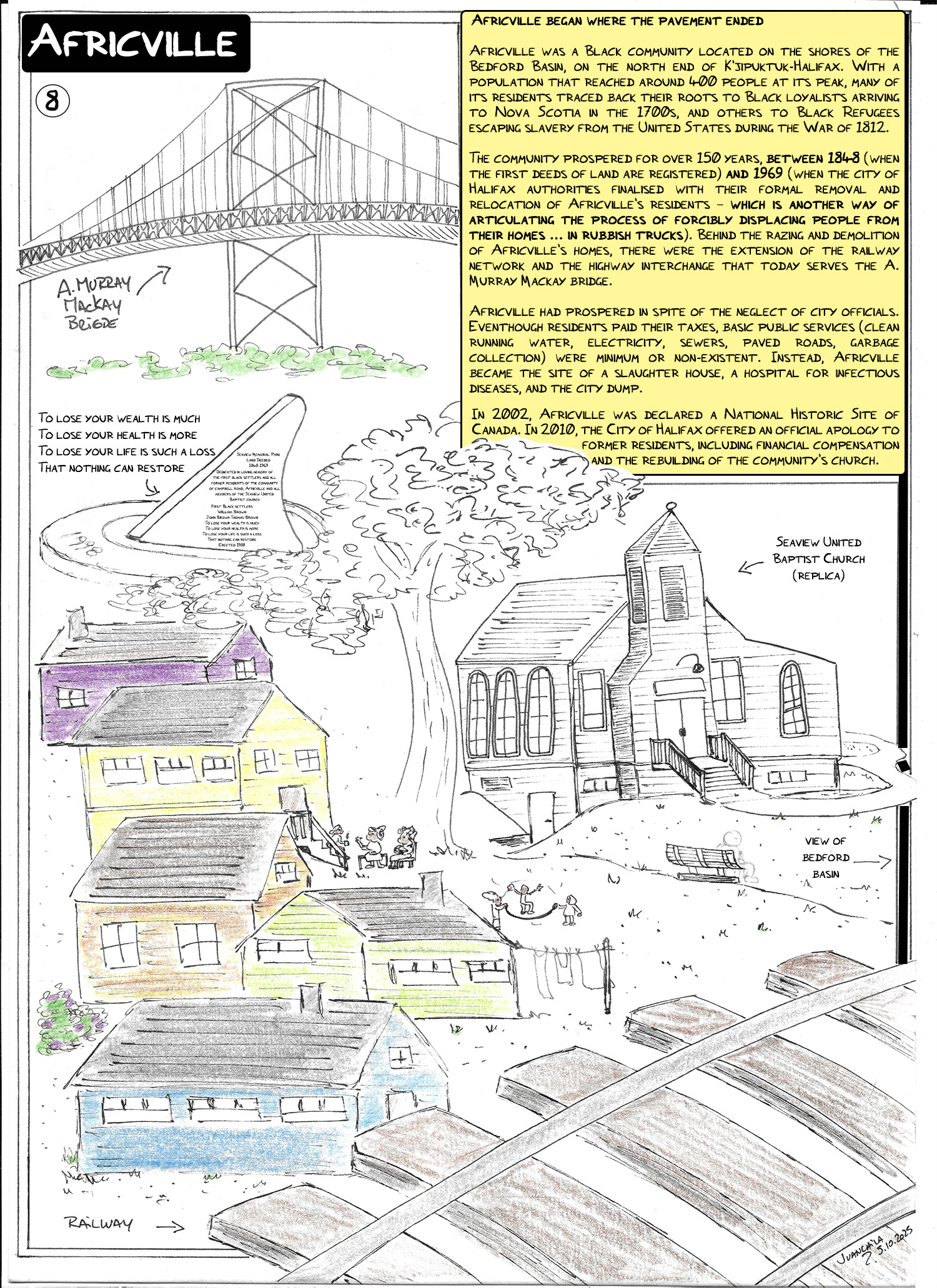

Panel 8 – Africville

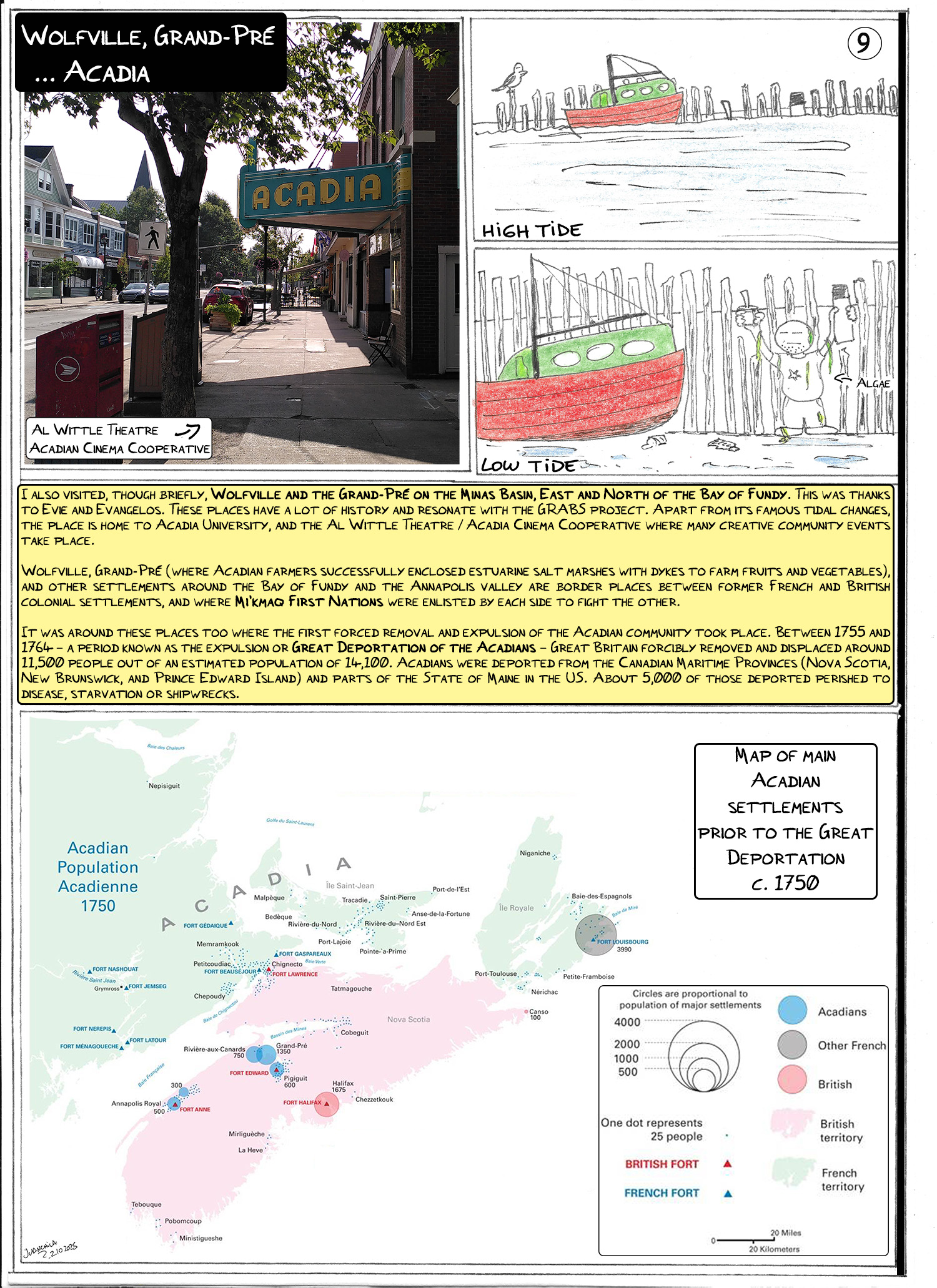

Panel 9 – Wolfville, Grand-Pré… Acadia

Panel 10 – Wela’lin, K’jipuktuk Nmul’tes

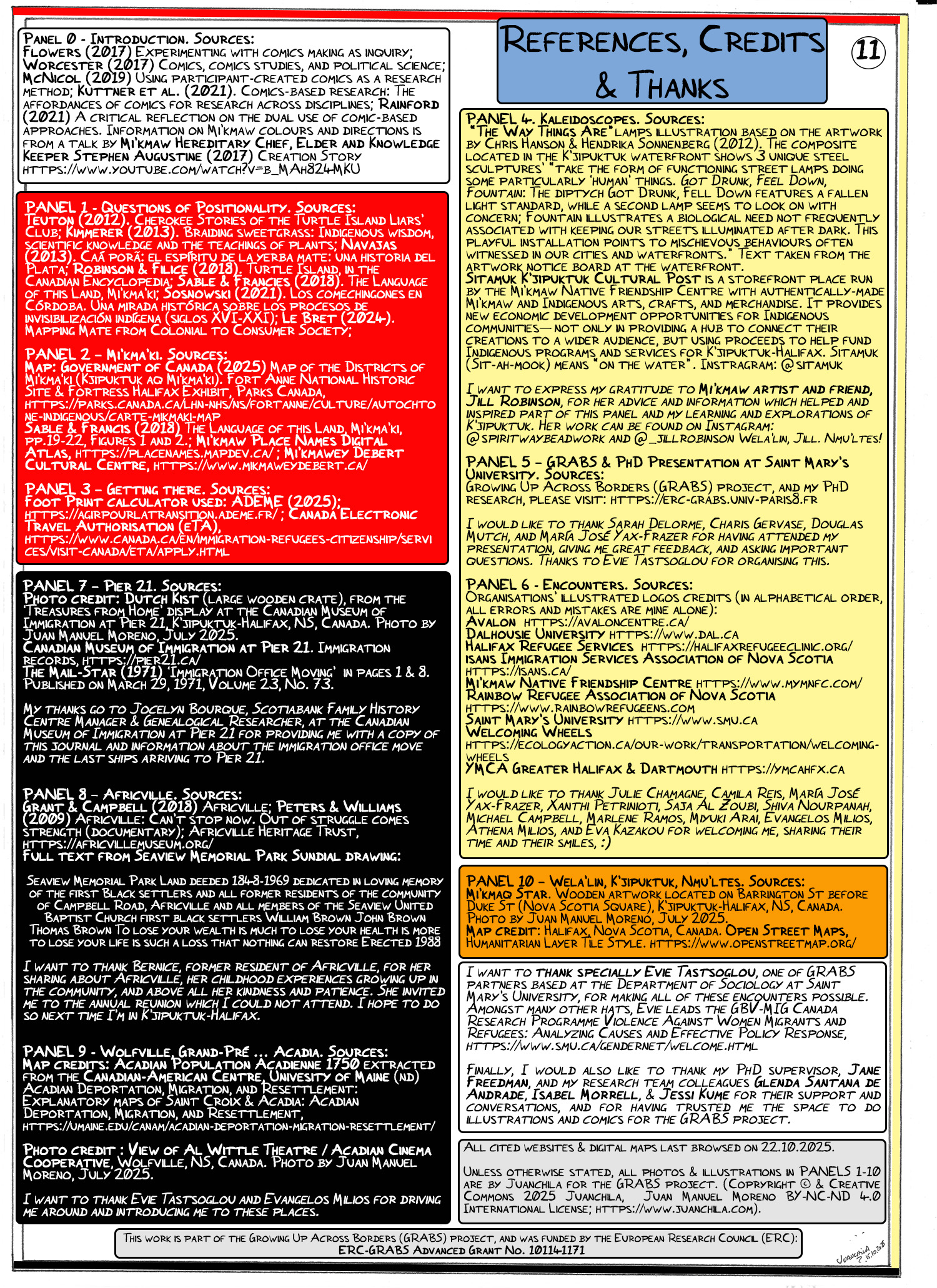

Panel 11 – References, Credits & Thanks

© 2025 Juanchila (Juan Manuel Moreno) & Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 International License