Veils of Silence : The Hidden Stories of Young Refugee Women in South Africa

I have been a refugee in South Africa since 2013. As an activist for refugee rights I have participated in different platforms and events that exposed me to traumatic experiences of refugees and women in particular. What struck me as different in the experiences of some of the young women we recently met in the course of our research is that they have been enduring violence and exclusion in South Africa, which includes experiences of rejection from their own community. Community networks are sometimes assumed to provide resources for coping or resilience for people in forced migration. Hearing from young women about rejection from their own communities struck me particularly. The women find themselves with nowhere to belong.

by Aron1

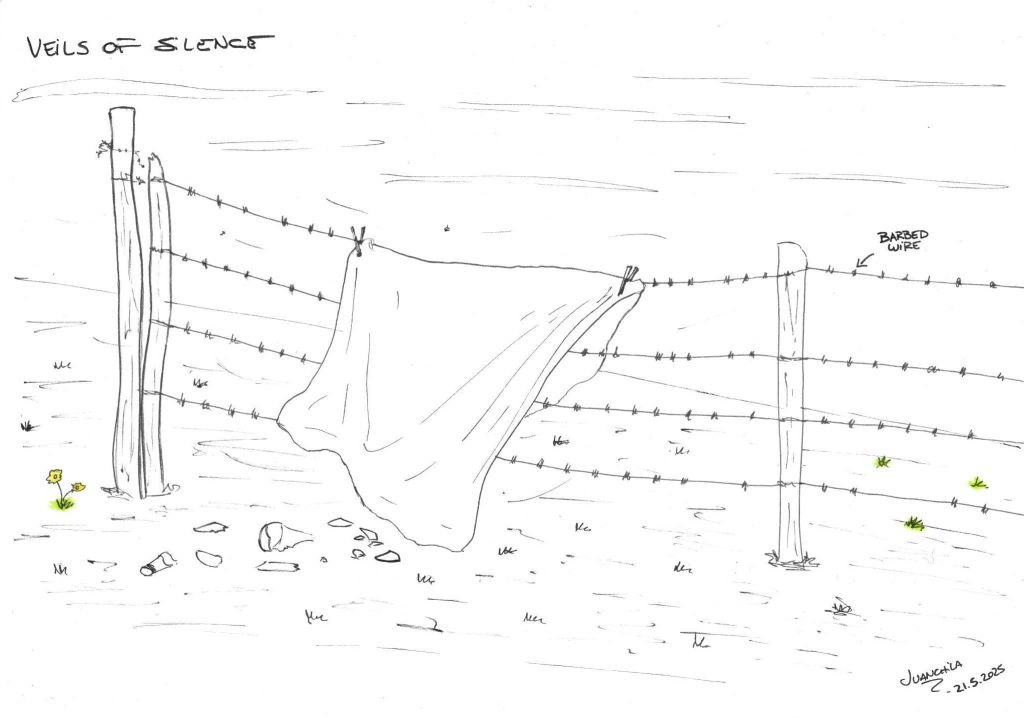

In the crowded South African cities, young refugee women walk among us—watched with raised eyebrows and quiet suspicion. Dressed in traditional attire, their heads covered with veils, their faces reveal the quiet strain of daily survival. But beneath the fabric lie untold stories—of abuse, rejection, and resilience. Their traumas remain hidden in plain sight.

During our recent fieldwork for the Growing up Across Borders (GRABS) project, we spoke with several young women who either migrated to South Africa as children or were born into migrant families. We sought to understand their experiences of displacement and their complex transitions to adulthood. What they shared with us was heartbreaking—narratives of exploitation, abandonment, and unimaginable courage.

One young mother’s story encapsulates the struggles of many. A refugee who fled her home country before the age of five, she now wears a veil not only as a symbol of her faith but also to cover the burn scars on her neck—scars left by the family of a man who had promised to marry her. Pregnant as a teenager, she was taken far from her mother and placed under the control of his family. There, she was isolated, abused, and silenced. It took incredible bravery to escape, to run for her life, and begin again. Her veil shields her trauma, yet it also speaks volumes: it protects her, conceals her suffering, and reveals just how unseen she has been.

Her story is not an exception. Many of the young women we met had similarly been uprooted—migrating with parents or relatives, only to find themselves neglected or abused. Promised safety, they instead encountered new forms of danger: forced labour, emotional manipulation, and sexual violence, often within the very homes meant to protect them.

Their marginalization is compounded by (and perhaps a consequence of) systemic failures. As children, many were documented under the names of adult caretakers. But once they reached 18, or completed matric, they were required to possess their own legal documents—something they often struggled to obtain. Despite having lived in South Africa for most or all of their lives, they are forced to undergo asylum interviews to determine their right to continue to hold asylum permits. As a result, some have become undocumented or labelled as “illegal,” after up to 15 years in the country. This precarious legal status has blocked their access to higher education and formal employment, deepening their exclusion from South African society.

Though these young women often feel more connected to South Africa than to their countries of origin, they hesitate to claim belonging. Their sense of exclusion starts early, when bullied at primary schools for not speaking local languages or for looking “different,” they quickly learn that they are seen as outsiders.

Caught between two worlds, they belong fully to neither. Within their own communities, they are sometimes judged, misunderstood, or left unsupported. Their pain is minimized, and their silence is mistaken for strength – resilient refugees. To the broader society, they are easily identifiable as foreigners—speaking differently, dressing differently, and carrying unfamiliar documents. This visibility makes them targets for xenophobic (Afrophobic) discrimination, particularly those who wear veils and traditional clothing.

Their veils and traditional clothing, only deepen their isolation. Within their own refugee circles, they wear these garments to maintain a connection to community and identity, yet still they are not embraced and supported. Outside of their communities, these same markers make them hypervisible—and amplify their situation of vulnerabilities.

The veil, then, becomes more than fabric. It is a layered symbol: of faith, of cultural heritage, but also of pain and silence.It hides scars—both physical and emotional—carried from years of betrayal, violence, and forced displacement. These are stories that are not told because they are too heavy, too complex, or too easily dismissed. And they live in a society that doesn’t care enough to hear their story.

But these young women deserve more than silence or pity. They deserve recognition, protection, and the right to live without fear, shame, or prejudice. They are not voiceless— they have simply been unheard. And we must ask ourselves: why is it so easy to look away?

- Aron Hagos Tesfai is a post-doctoral researcher based at HEARD, University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and a team member of the GRABS project.

↩︎