Borders Crafted with Care: Biscuits, Trains and Little Ships

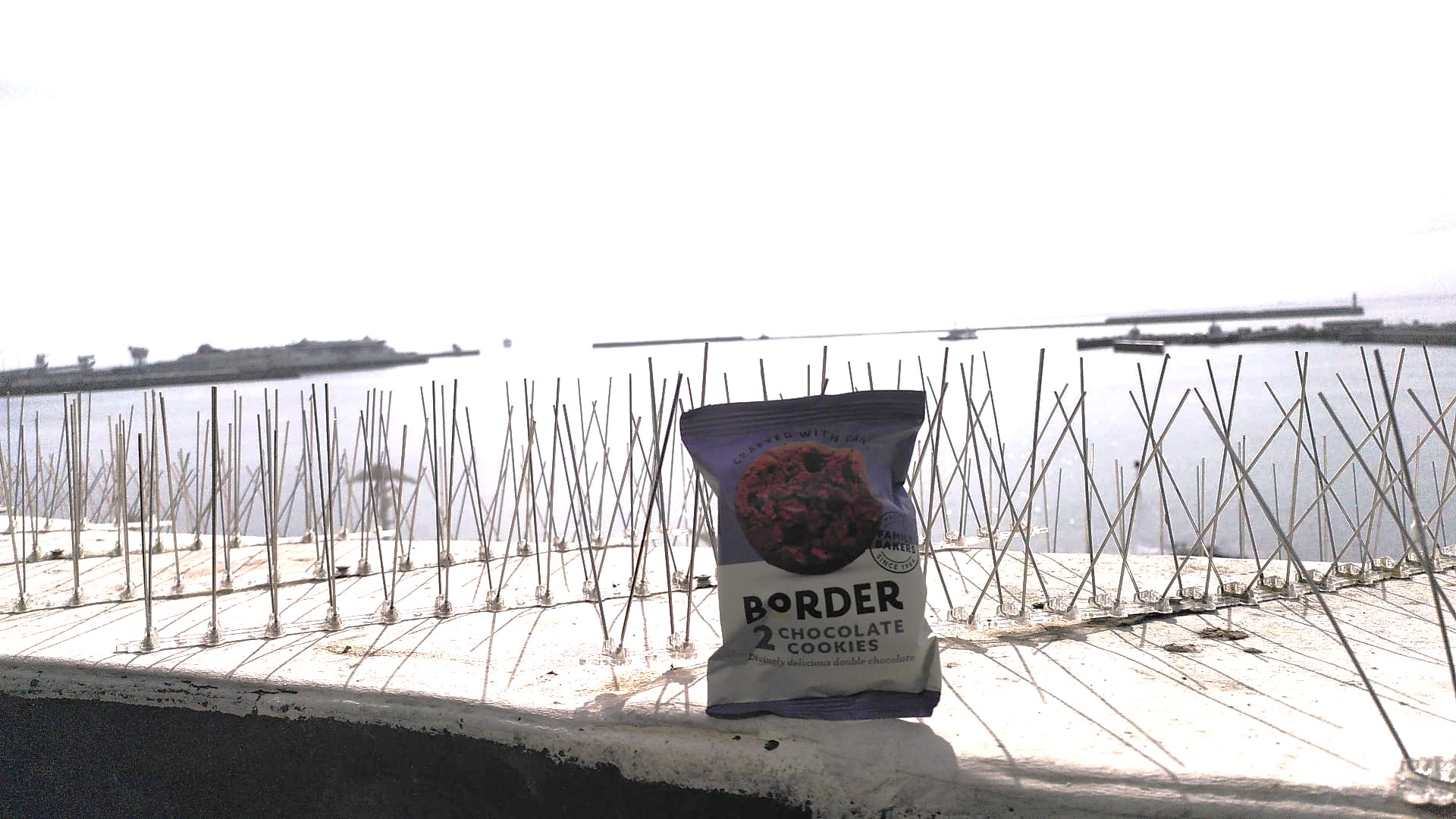

The title of this piece is inspired by the packaging of the biscuits provided to our team while staying in Dover during a scoping trip in the UK. The biscuits were called “Borders” with the tagline: “crafted with care”. Besides the irony of biscuits in Dover being named “Borders,” the meaning wasn’t entirely off. Borders are crafted—constructed—based on lines of race, gender, class, age or religion. Not everyone crosses a border in the same way, and not everyone is impacted by the border in the same way.

And this was true for me as a researcher as well. I crossed the border differently than the people on the move I met and did research with. My positionality is different as I hold visa privileges that are evident even in the simple act of taking a train. In January, our team had been in Calais, on the other side of the Channel, where people on the move were stuck, facing evictions and intimidation by the police while trying to cross. By May, we were taking the train from France to the UK, crossing that same Channel. Ten minutes were enough to apply for a visa – something that an EU passport holder could do quickly and easily from a phone – which then led to comfortably sitting on a train seat. The same is not possible for people on the move, for whom the Channel represents a barrier—a border. A perhaps banal assumption to be made about borders is that they are not simply lines dividing territories; they acquire social, political, and cultural significance. Critical border studies have redefined the function of borders not as merely demarcating territory, but as regulating the movement of people, capital, and rights across space and time (Balibar, 2002[1]; Mezzadra e Neilson, 2013[2]). Borders select and (im)mobilise, enforcing limitations and privileges in unequal ways.

The Eurotunnel we crossed—opened in 1994—reduced travel time between France and Britain to just 35 minutes. Meanwhile, in Calais and Dunkirk, it may take months for people on the move to even attempt a crossing. Many are ultimately intercepted and pushed/pulled back to the northern French coast. Those who do manage to cross often face a long and uncertain asylum process, which can take months or even years. Crossing the Channel is not only difficult—it can also be deadly. Some people attempting the journey have been arrested or lost their lives. When the tunnel was still under construction, many tried to make the journey through the tunnel itself—sometimes never to see the light again. To those with visas, the border grants the privilege of high-speed travel; to others, it enforces the repression of mobility.

Building on the argument that borders carefully craft systems of inequality—producing hierarchies and determining who can move safely and who cannot—the contrast between the historical memory of the Dunkirk rescue and the present-day criminalisation of movement is significant. From Calais and Dunkirk, the white cliffs of Dover represent the end of a long, dangerous route. But those same cliffs meant something else in 1940 during Operation Dynamo. It is the case of 1,000 vessels sailing through the Channel to rescue more than 338,000 British and Allied troops stranded on the beaches of Dunkirk. Every five years the Association of Dunkirk Little Ships (ADLS) organises a commemorative crossing described as “a poignant tribute to the bravery and sacrifice” of those involved. Eighty-five years later, other little boats are still trying to cross. So far, 303 people have lost their lives in these attempts—54 of them in 2024 alone. These are only the recorded deaths. On the day the GRABS team was in Dover, the Dunkirk Little Ships commemoration was taking place — while, on that same day, two people lost their lives attempting to cross the Channel. Some boats are portrayed as heroic and celebrated; others are seen as threats and are demonised.

Borders are enforced differently and by their differential enforcement much is revealed about the racialized, gendered and classed divides that borders today seek to enforce (Wonders, 2006)[3]. A testimony to the fact that borders are indeed crafted: it is the same sea, crossed by different people in different boats or through the same (euro)tunnel. These borders are carefully crafted, but care is reserved only for some.